Israeli Bomblets Plague Lebanon

By MICHAEL SLACKMAN

Published: October 6, 2006

New York Times

Published: October 6, 2006

New York Times

What did this small boy do to Israel? He's not a "terrorist." He's a victim of a cruel and godless world. We would not condone a suicide bombing in an Israeli night club, and we cannot allow cluster bombs in civilian areas. This boy is not the problem, but reckless violence may turn him into an Israeli nightmare!

What did this small boy do to Israel? He's not a "terrorist." He's a victim of a cruel and godless world. We would not condone a suicide bombing in an Israeli night club, and we cannot allow cluster bombs in civilian areas. This boy is not the problem, but reckless violence may turn him into an Israeli nightmare!Paul Taggart/World Picture Network

Abbass Ahmad Sultan, 14, resting at a neighbor's house after

being treated in a hospital for shrapnel wounds.

Abbass Ahmad Sultan, 14, resting at a neighbor's house after

being treated in a hospital for shrapnel wounds.

BEIRUT, Lebanon, Sept. 29 - Since the war between Israel and Hezbollah ended in August, nearly three people have been wounded or killed each day by cluster bombs Israel dropped in the waning days of the war, and officials now say it will take more than a year to clear the region of them.

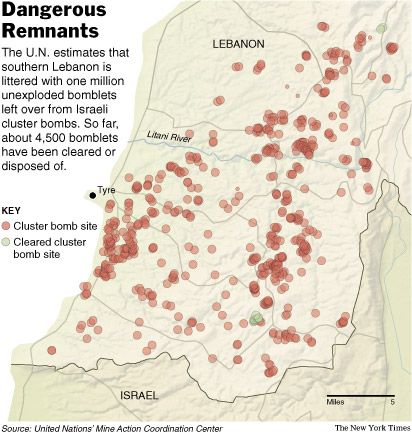

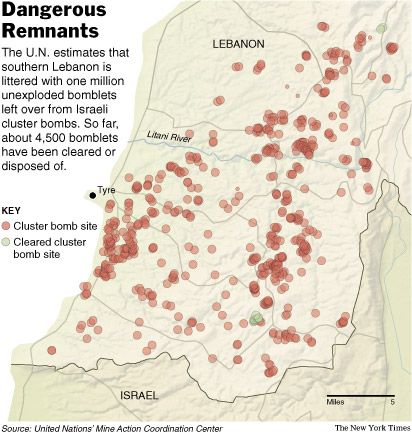

United Nations officials estimate that southern Lebanon is littered with one million unexploded bomblets, far outnumbering the 650,000 people living in the region. They are stuck in the branches of olive trees and the broad leaves of banana trees. They are on rooftops, mixed in with rubble and littered across fields, farms, driveways, roads and outside schools.

As of Sept. 28, officials here said cluster bombs had severely wounded 109 people - and killed 18 others.

As of Sept. 28, officials here said cluster bombs had severely wounded 109 people - and killed 18 others.

Muhammad Hassan Sultan, a slender brown-haired 12-year-old, became a postwar casualty when the shrapnel from a cluster bomb cut into his head and neck.

He was from Sawane, a hillside village with a panoramic view of terraced olive farms and rolling hills. Muhammad was sitting on a hip-high wall, watching a bulldozer clear rubble, when the machine bumped into a tree.

A flash of a second later he was fatally injured when a cluster bomblet dropped from the branches.

"I took Muhammad to the hospital in my car, but he was already dead," said Yousef Ftouni, a resident of the village.

The entire village was littered with the bomblets, and as Mr. Ftouni recounted Muhammad's death, the Lebanese Army worked its way through an olive grove, blowing up unexploded munitions in a painfully slow process of clearance.

Cluster bombs are legal if aimed at military targets and are very effective, military experts say. Nonetheless, Israel has been heavily criticized by United Nations officials, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch for using cluster bombs, because they are difficult to focus exclusively on military targets. Israel was also criticized because it fired most of its cluster bombs in the last days of the war, when the United Nations Security Council was negotiating a resolution to end the conflict.

Officials calculate that if they are lucky, and money from international donors does not run out, it will take 15 months to clear the area. There are now about 300 Lebanese Army soldiers and 30 other clearance teams, each of up to 30 experts, working on the problem of unexploded bomblets.

The United Nations Mine Action Coordination Center in southern Lebanon recorded 745 locations across the south where unexploded bombs had been found. Of the million estimated to be scattered around, so far 4,500 have been disposed of, according to the center.

"Our priority at the moment is to clean houses, main roads and gardens so that the displaced people can return to their villages," said Col. Mohammad Fahmy, head of the national mine clearing office. "The next stage will be cleaning agricultural lands."

In Lebanon there are two explanations of why Israel unleashed cluster bombs at the end of the war: to inflict as much damage as possible on Hezbollah before withdrawing, or to litter the south with unexploded cluster bombs as a strategy to keep people from returning right away.

The United States has sold cluster bombs to Israel in the past and says it is investigating whether Israel's use of cluster bombs in its war with Hezbollah violated a secret agreement that restricted when they could be used.

The final days of the war - a conflict that began when Hezbollah launched rockets from Lebanon into northern Israel and sent militiamen across the border to capture Israeli soldiers - were marked by a huge Israeli offensive. Israel hoped its final push would, in part, help force the Security Council to adopt a tougher resolution on Hezbollah than appeared to be taking shape.

Israel has said it leafleted areas before bombing and provided Lebanon with maps of potential cluster bomb locations to help with the clearing process. United Nations officials in Lebanon say the maps are useless.

The Israeli newspaper Haaretz published an article on Sept. 12 anonymously quoting the head of a rocket unit in Lebanon who was critical of the decision to use cluster bombs. "What we did was insane and monstrous; we covered entire towns in cluster bombs," Haaretz quoted the commander as saying.

Repeated efforts to get Israeli officials to explain the rationale behind the use of the bombs have proved fruitless, with spokesmen referring all queries to short official statements arguing that everything done conformed with international law.

In Lebanon the problem of the unexploded munitions is magnified by the desire to return to villages and lives in a region that is effectively booby-trapped. People want to begin rebuilding and harvest their crops. In some cases they have tried to clear the bomblets themselves, and some people have begun charging a small fee to clear away bombs - a practice that officials have discouraged as dangerous.

But the people are desperate.

"If I lost the season for olives and the wheat, I have no money for the winter," said Rida Noureddine, 54, who farms a small patch of land on the main road in the village of Kherbet Salem. There was a small black object at the entrance to his farm, and he thought it was a cluster bomb.

"I feel as if someone has tied my arms, or is holding me by my neck, suffocating me because this land is my soul," he said.

The bomblets, about the size of a D battery, can be packed into bombs, missiles or artillery shells. When the delivery system detonates, the bomblets spread like buckshot across a large area, making them difficult to aim with precision. A fact sheet issued by the Mine Action Coordination Center says cluster bombs have an official failure rate of 15 percent.

That means that 15 percent of the bomblets remain as hazards. According to the fact sheet, the failure rate in this war is estimated to be around 40 percent. "We estimate there are one million," said Dalya Farran, the community liaison officer of the mine action center.

Ms. Farran has worked at the center for nearly three years. It was set up in 2000 to help deal with the mines and unexploded ordnance left behind after the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon and from other wars.

After this war, Ms. Farran said, there are two types of cluster bomb fragments across the south. The most commonly found type is known as M42, a deceptively small device resembling a light socket.

She said a large percentage of the unexploded bomblets were made in America, while some were produced in Israel. Each one has a white tail dangling off the back, like the tail of a kite. As they fall to the ground, the tail spins and unscrews the firing pin.

When the device hits, the front end fires a huge slug while the casing blasts apart into a spray of deadly metal fragments. When they fail to detonate they cling to the ground, and with their white tails look deceptively like toys, so children are often those who are injured.

"This is what they are living with every day," said Simon Lovell, a supervisor with one of the clearance teams as he looked at five unexploded bomblets poking out of the soft, rocky soil of the Hussein family farm.

Across the street, Hussein Muhammad, 48, at home with his wife and four children, waited for the clearance team. His olive trees were heavy with fruit, but he could not tend to the harvest.

"I feel that the land has become my enemy," he said. "It represents a danger to my life and my kids' lives."

Nada Bakri contributed reporting from Lebanon.

United Nations officials estimate that southern Lebanon is littered with one million unexploded bomblets, far outnumbering the 650,000 people living in the region. They are stuck in the branches of olive trees and the broad leaves of banana trees. They are on rooftops, mixed in with rubble and littered across fields, farms, driveways, roads and outside schools.

As of Sept. 28, officials here said cluster bombs had severely wounded 109 people - and killed 18 others.

As of Sept. 28, officials here said cluster bombs had severely wounded 109 people - and killed 18 others.

Muhammad Hassan Sultan, a slender brown-haired 12-year-old, became a postwar casualty when the shrapnel from a cluster bomb cut into his head and neck.

He was from Sawane, a hillside village with a panoramic view of terraced olive farms and rolling hills. Muhammad was sitting on a hip-high wall, watching a bulldozer clear rubble, when the machine bumped into a tree.

A flash of a second later he was fatally injured when a cluster bomblet dropped from the branches.

"I took Muhammad to the hospital in my car, but he was already dead," said Yousef Ftouni, a resident of the village.

The entire village was littered with the bomblets, and as Mr. Ftouni recounted Muhammad's death, the Lebanese Army worked its way through an olive grove, blowing up unexploded munitions in a painfully slow process of clearance.

Cluster bombs are legal if aimed at military targets and are very effective, military experts say. Nonetheless, Israel has been heavily criticized by United Nations officials, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch for using cluster bombs, because they are difficult to focus exclusively on military targets. Israel was also criticized because it fired most of its cluster bombs in the last days of the war, when the United Nations Security Council was negotiating a resolution to end the conflict.

Officials calculate that if they are lucky, and money from international donors does not run out, it will take 15 months to clear the area. There are now about 300 Lebanese Army soldiers and 30 other clearance teams, each of up to 30 experts, working on the problem of unexploded bomblets.

The United Nations Mine Action Coordination Center in southern Lebanon recorded 745 locations across the south where unexploded bombs had been found. Of the million estimated to be scattered around, so far 4,500 have been disposed of, according to the center.

"Our priority at the moment is to clean houses, main roads and gardens so that the displaced people can return to their villages," said Col. Mohammad Fahmy, head of the national mine clearing office. "The next stage will be cleaning agricultural lands."

In Lebanon there are two explanations of why Israel unleashed cluster bombs at the end of the war: to inflict as much damage as possible on Hezbollah before withdrawing, or to litter the south with unexploded cluster bombs as a strategy to keep people from returning right away.

The United States has sold cluster bombs to Israel in the past and says it is investigating whether Israel's use of cluster bombs in its war with Hezbollah violated a secret agreement that restricted when they could be used.

The final days of the war - a conflict that began when Hezbollah launched rockets from Lebanon into northern Israel and sent militiamen across the border to capture Israeli soldiers - were marked by a huge Israeli offensive. Israel hoped its final push would, in part, help force the Security Council to adopt a tougher resolution on Hezbollah than appeared to be taking shape.

Israel has said it leafleted areas before bombing and provided Lebanon with maps of potential cluster bomb locations to help with the clearing process. United Nations officials in Lebanon say the maps are useless.

The Israeli newspaper Haaretz published an article on Sept. 12 anonymously quoting the head of a rocket unit in Lebanon who was critical of the decision to use cluster bombs. "What we did was insane and monstrous; we covered entire towns in cluster bombs," Haaretz quoted the commander as saying.

Repeated efforts to get Israeli officials to explain the rationale behind the use of the bombs have proved fruitless, with spokesmen referring all queries to short official statements arguing that everything done conformed with international law.

In Lebanon the problem of the unexploded munitions is magnified by the desire to return to villages and lives in a region that is effectively booby-trapped. People want to begin rebuilding and harvest their crops. In some cases they have tried to clear the bomblets themselves, and some people have begun charging a small fee to clear away bombs - a practice that officials have discouraged as dangerous.

But the people are desperate.

"If I lost the season for olives and the wheat, I have no money for the winter," said Rida Noureddine, 54, who farms a small patch of land on the main road in the village of Kherbet Salem. There was a small black object at the entrance to his farm, and he thought it was a cluster bomb.

"I feel as if someone has tied my arms, or is holding me by my neck, suffocating me because this land is my soul," he said.

The bomblets, about the size of a D battery, can be packed into bombs, missiles or artillery shells. When the delivery system detonates, the bomblets spread like buckshot across a large area, making them difficult to aim with precision. A fact sheet issued by the Mine Action Coordination Center says cluster bombs have an official failure rate of 15 percent.

That means that 15 percent of the bomblets remain as hazards. According to the fact sheet, the failure rate in this war is estimated to be around 40 percent. "We estimate there are one million," said Dalya Farran, the community liaison officer of the mine action center.

Ms. Farran has worked at the center for nearly three years. It was set up in 2000 to help deal with the mines and unexploded ordnance left behind after the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon and from other wars.

After this war, Ms. Farran said, there are two types of cluster bomb fragments across the south. The most commonly found type is known as M42, a deceptively small device resembling a light socket.

She said a large percentage of the unexploded bomblets were made in America, while some were produced in Israel. Each one has a white tail dangling off the back, like the tail of a kite. As they fall to the ground, the tail spins and unscrews the firing pin.

When the device hits, the front end fires a huge slug while the casing blasts apart into a spray of deadly metal fragments. When they fail to detonate they cling to the ground, and with their white tails look deceptively like toys, so children are often those who are injured.

"This is what they are living with every day," said Simon Lovell, a supervisor with one of the clearance teams as he looked at five unexploded bomblets poking out of the soft, rocky soil of the Hussein family farm.

Across the street, Hussein Muhammad, 48, at home with his wife and four children, waited for the clearance team. His olive trees were heavy with fruit, but he could not tend to the harvest.

"I feel that the land has become my enemy," he said. "It represents a danger to my life and my kids' lives."

Nada Bakri contributed reporting from Lebanon.